Mobility Transition & Space

In July 2018, the Dutch Climate Agreement has been published, in which a large group of stakeholders made agreements on how to meet the Paris treaty. With a consortium of spatial design firms, FABRICations investigated the spatial consequences and opportunities of this agreement.

-

Location

The NetherlandsYear

2018 -

Ministerie van Infrastructuur en Waterstaat

Ministerie van Economische Zaken en Klimaat -

Dirk Sijmons

H+N+S

Generation.Energy

Studio Marco Vermeulen

NRGlab

Bright

Andy van den Dobbelsteen -

Design Directors

Eric Frijters

Olv KlijnProject leader

Rens WijnakkerTeam

Max Augustijn

Caterina Vetrugno

Wesley Verhoeven

Johnatan Subendran

“Corridor landscapes, bundles of highways, railroads, waterways and bike routes, will transform into energy landscapes where energy is harvested, transported and used.”

— Eric Frijters

In July 2018, the Dutch Climate Agreement has been published, in which a large group of stakeholders made agreements on how to meet the Paris treaty. With a consortium of spatial design firms, FABRICations investigated the spatial consequences and opportunities of this agreement. FABRICations joined the mobility table, in which we explored the effects of the mobility transition for land use, but also collected and generated ideas on how to reduce energy use in mobility with spatial planning and design. Approximately 2/3 of the reduction in CO2 emissions should come from the transition to renewable fuels.

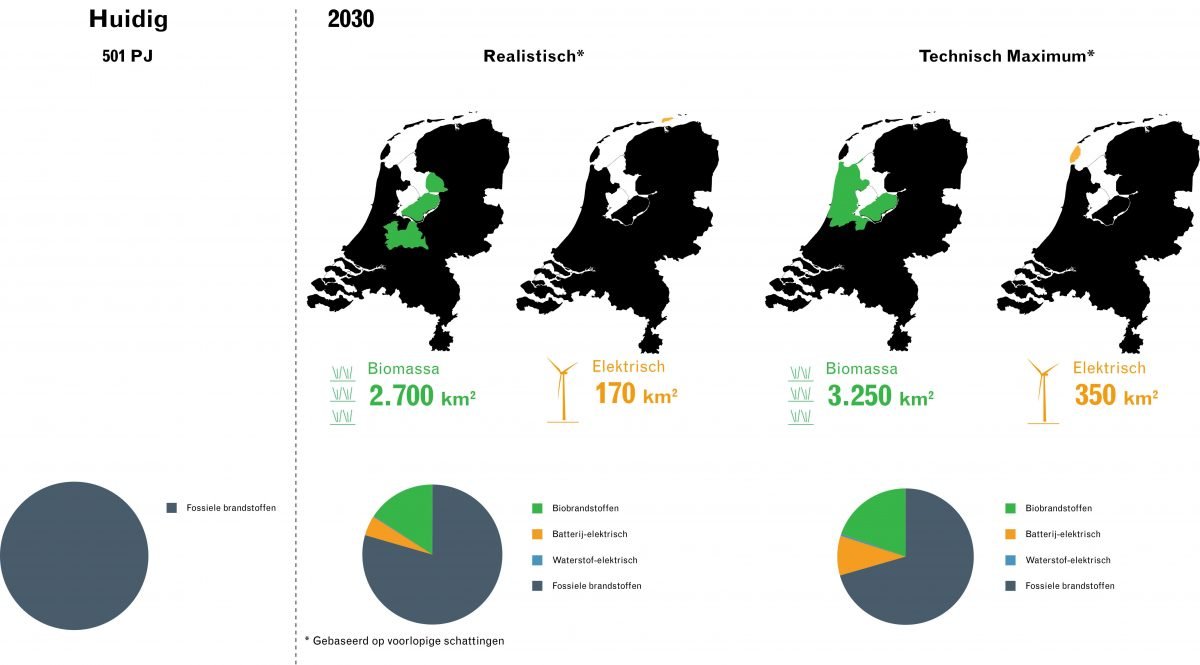

The fuel transition does not only take place ‘under the hood’. It has large spatial effects, since different fuel mixes (hydrogen, biofuels and battery) have large consequences on the required space for energy production. Where bio fuels need space for crops to grow, electric mobility needs wind turbines to supply energy. The spatial implications are huge: to meet the proposed amount of energy generated by bio fuels in 2030, it is necessary to grow crops on an area covering two Dutch provinces. The infrastructure necessary to charge/fuel cars also has strong spatial implications. The other 1/3 of emission reduction has to come from a change in behavior.

Here are more direct relations between the mobility transition and space. An integrated and future-ready urban mobility plan in combination with smart, compact urbanism can result in a significant reduction of CO2 emissions. Inhabitants of dense areas spent 40% less energy on mobility, then inhabitants of urban extensions. This has partly to do with the amount services on walking distance, but also with a lack of accessibility. The biggest opportunities for combining mobility and energy infrastructure are on a regional level, for instance with regional heat networks and cycling highways.

On a national level, energy infrastructure has its own pipe system which is on a distance from highways and railroads. On a lower scale level the distances and destinations of energy flows match the ambitions for many new bike-highways and provincial roads. This and much more information can be found in the document ‘Ruimte in het Klimaatakkoord’, available here.